A Clinic Worth Building: A Global Blueprint for Integrating Complementary and Integrative Medicine (CAIM) into Modern Healthcare Systems (Part 1)

- Editor

- Jun 22, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2025

Dr. Qaisar J. Qayyum

Chief Editor, Noor Journal of Complementary and Contemporary Medicine, Clinical Assistant Professor, Oklahoma, USA. Email: chiefeditor@njccm.org

Introduction:

Despite rapid advances in diagnostics, therapeutics, and digital technologies, modern healthcare systems remain burdened by rising costs, escalating rates of chronic disease, and growing patient dissatisfaction. At the same time, the limitations of industry-funded research, often misaligned with real-world clinical outcomes, have become increasingly apparent. Many patients find that their lived experience does not match the optimistic claims of clinical trials, prompting a critical question: Is there anything else?

For many, the answer is unclear, or simply not available, within conventional models. Biomedicine offers unmatched strengths in acute and emergency care. But when symptoms are vague, multifactorial, or chronic, the system’s answers often fall short.

A Complementary and Integrative Medicine (CAIM) department offers a clinical philosophy centered on the whole person, not just the disease. It emphasizes therapeutic alliance, functional recovery, and pluralism in therapeutic tools. Yet in most hospital systems, complementary care remains fragmented, optional, or altogether absent. Patients are often left to self-navigate, self-diagnose, and self-medicate, frequently without clinical oversight. This can lead to adverse outcomes, including the misattribution of side effects to conventional medicine, when in fact they may stem from unregulated or inappropriate use of complementary therapies.

When physicians lack familiarity with CAIM, or hold biased views against it, patients are left with little recourse but to act as their own healers. This exposes them to unnecessary risks and undermines coordinated care.

This paper proposes an institutional framework for a Department of Complementary and Integrative Medicine: a real-world, physician-led, ethically governed structure to formally support complementary care wherever it is warranted, requested, or necessary.

Reclaiming Health Sovereignty:

CAIM as a Strategic Policy Blueprint

We are living through a historic reckoning with federal health agencies and biomedical orthodoxy. Trust in centralized institutions is collapsing, not just among the public, but within scientific and clinical circles. People are asking hard questions: Have pharma-driven models overreached? Why are chronic disease, mental illness, and therapeutic fatigue still rising despite record spending? Where is the innovation patients actually want?

In this vacuum, new models are gaining ground, and CAIM is one of them. But this isn’t just about herbs and acupuncture. A CAIM department is a blueprint for health sovereignty. It gives hospitals and governments the power to reclaim clinical authority from over-centralized, pharma-dependent systems and to reintroduce trusted, culturally grounded, patient-preferred therapies, under rigorous, physician-led governance.

This framework aligns with the current political moment: decentralization, transparency, and personal choice. It resonates with lawmakers and reformers who no longer trust top-down medical gatekeeping and want solutions that reflect their values, not corporate scripts. This is not fringe. It’s strategic. It’s scalable. It’s popular.

For legislators, health boards, and national agencies ready to take control of the healthcare narrative, this proposal is not merely necessary, it is long overdue. It delivers a ready-made, legally defensible model to build safer, pluralistic, and more accountable systems of care, without waiting for permission from institutions the public no longer believes in.

Why CAIM Is No Longer Optional:

A Clinical and Institutional Imperative

The expansion of CAIM is not a hopeful experiment, it is a pragmatic response to systemic gaps in modern healthcare. Chronic disease, therapeutic fatigue, mental health strain, and cultural mismatch are driving patients toward complementary approaches, with or without clinical guidance. Ignoring this shift doesn’t preserve safety, it forfeits leadership.

Hospitals, health systems, and governments that integrate CAIM under structured, physician-led governance aren’t taking risks, they’re managing them. They’re regaining control over a rapidly growing parallel industry, improving patient satisfaction, and rebuilding institutional trust in a landscape marked by disillusionment and demand for agency.

The Clinical Rationale for Integration:

Chronic pain, autoimmune complaints, mental health conditions, and medically unexplained symptoms continue to affect a growing proportion of adults. Published survey data show that many individuals seek complementary approaches specifically for these conditions, often after conventional treatments have proven insufficient or unsatisfactory [1]. CAIM offers alternatives or adjuncts to these paths by focusing on body–mind–spirit integration and functional resilience.

The World Health Organization’s Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine (2019), which reflects input from 179 member states, provides one of the most comprehensive global overviews of traditional, complementary, and integrative health practices. The report underscores the need for institutional integration, regulatory clarity, and evidence-based validation of these modalities within national health systems [2].

Current estimates indicate that between 30–50% of adults in high-income countries have used some form of complementary or alternative care [3,4]. This reflects not only cultural trends but also a growing unmet need within mainstream healthcare. The U.S. Veterans Health Administration, recognizing this, has implemented a multicenter Whole Health initiative across its medical centers. According to one evaluation, 26% of veterans with chronic pain used complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies. While many of these services were initially accessed in the community, an increasing proportion are now being delivered directly within VA facilities, due to the hiring of CIH providers at pilot sites [5].

Major centers like the Mayo Clinic and Memorial Sloan Kettering have already established dedicated integrative medicine departments embedded within their hospital systems [6,7]. Peer-reviewed data support this shift. Studies show that CAIM is associated with improved symptom control, decreased opioid reliance, fewer hospital days, and better patient satisfaction [8,9]. Improved physician satisfaction and reductions in burnout are also reported in environments where clinicians have access to a broader range of therapeutic modalities [10].

Department Structure and Leadership:

The proposed department is led by a medical doctor (MD or DO) with both clinical and academic interest in integrative modalities. The lead physician provides oversight for clinical care, regulatory compliance, and patient assignment to appropriate CAIM modalities.

Complementary specialists, such as homeopaths, herbalists, acupuncturists, and practitioners of Ayurveda, Hikmat/Unani, and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), function as Independent Licensed Professionals (ILPs) within the department. ILPs function under shared clinical governance within their licensure scope and do not independently manage primary diagnosis or prescription unless legally authorized. Each contributes modality-specific recommendations under the shared clinical governance of the lead physician. Importantly, this structure is collaborative, not hierarchical. It preserves each discipline’s autonomy while maintaining biomedical safety standards.

Patient Selection and Referral Criteria:

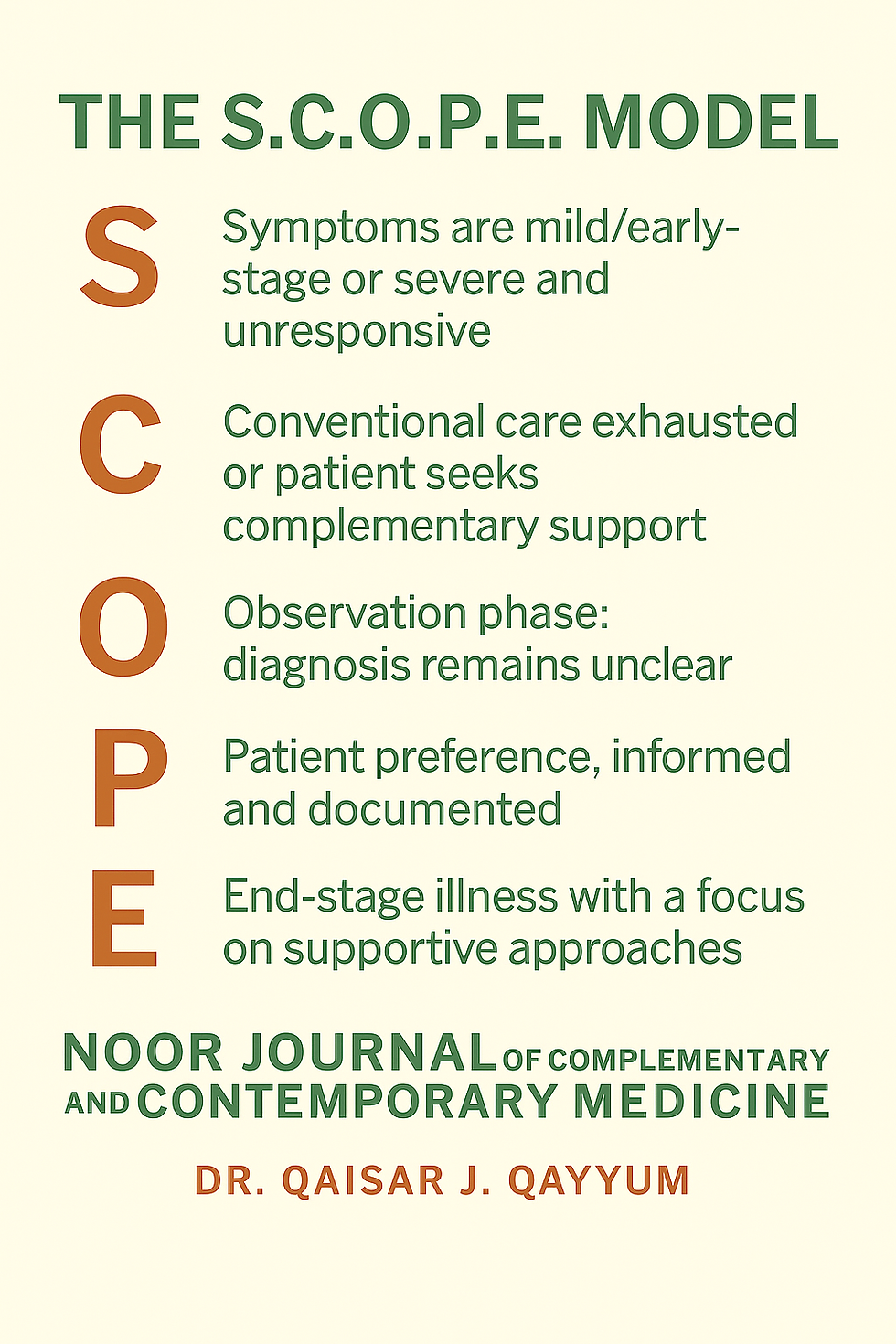

The S.C.O.P.E. Model

Referrals to the CAIM department follow clearly defined clinical logic. The S.C.O.P.E. model outlines five eligible scenarios:

S – Symptoms are either mild or early-stage, and the patient is not yet ready to begin conventional therapy; or they are severe and unresponsive to standard treatment.

C – Conventional care has been exhausted, yet the disease continues to progress despite adherence to prescribed treatment, or the patient wishes to supplement ongoing care with CAIM.

O – Observation phase, in which diagnosis remains unclear and complementary therapy is only used when deemed medically appropriate and with clear documentation that complementary care does not delay or interfere with critical diagnostics and urgent treatments.

P – Patient preference, informed and documented, to pursue CAIM despite the availability of conventional options.

E – End-stage disease, with limited options remaining and a desire for comfort, dignity, or spiritual alignment through supportive CAIM approaches.

These scenarios represent familiar clinical challenges where patients may be open to complementary options, particularly when conventional treatments are limited or ineffective. Documenting such cases brings structure, safeguards, and clinical accountability to the referral process.

This proposed model offers a practical, testable framework for patient selection that can be piloted across diverse clinical settings, refined through implementation experience, and potentially standardized for broader institutional use.

Daily Workflow and Clinical Operations:

Each clinical day begins with a structured morning huddle involving the lead MD/DO, nurse case manager, and CAIM clinicians. They review the day’s scheduled patients, these are not walk-ins, but referred cases with documented histories and clear therapeutic goals. The referring physician has already discussed the rationale with the patient and formally requested evaluation, ensuring the system functions like any other subspecialty consult service.

Treatment suggestions are proposed collaboratively, for example, individualized homeopathy for long COVID-related fatigue, acupuncture for diabetic neuropathy, or herbal tonics for digestive dysregulation. The lead physician evaluates each proposal for safety, supporting evidence, and compatibility with the patient’s ongoing care and the scope of the relevant CAIM discipline. Approved interventions are integrated into the electronic medical record (EMR) and monitored through structured follow-up.

Importantly, care remains fully integrated, not fragmented. Patients are never simply handed off; they stay anchored within the formal medical system, ensuring they receive proper guidance and are not left to navigate unregulated or potentially unsafe therapies on their own. This structure protects patients from misinformation and risk, which often emerge when conventional care offers no support for those exploring complementary options. All complementary care plans and progress notes are documented in medically appropriate formats within the shared EMR. Standardized, legally binding consent forms, risk disclosures, and follow-up metrics ensure accountability and continuity.

Ethical and Clinical Boundaries:

Ethics and patient safety are foundational to the operation of a CAIM department. All interventions must adhere to clinical protocols designed to ensure that therapies are not only appropriate but responsibly applied within the medical framework of care.

1. Explicit Informed Consent: Patients are required to provide written, culturally sensitive, and medically appropriate informed consent before initiating any complementary intervention. Consent forms detail the modality offered, its rationale, anticipated benefits, potential side effects, and alternative options, including choosing no intervention. Practitioners are trained to avoid coercion or exaggerated claims and instead foster informed, patient-led decision-making.

2. Drug-Herb and Modality Interaction Review: Each CAIM provider, while independently licensed and responsible for their treatment plans, is expected to proactively consult the lead physician, and when appropriate, a clinical pharmacist, regarding any potential interactions with the patient’s current medications. Given that some side effects may be unknown, and many complementary therapies have not been studied alongside conventional drugs, treatment decisions are guided by traditional use, clinical experience, and expert consensus, in alignment with current pharmacological knowledge and institutional medication safety guidelines . In cases of uncertainty, collaborative judgment and close monitoring help ensure patient safety.

3. Adjustments for Comorbidities and Contraindications: Each intervention is carefully tailored to the patient’s broader clinical picture. For example, individuals with renal impairment may require exclusion of nephrotoxic herbs, while those with bleeding disorders may not be suitable candidates for acupuncture unless the risk is demonstrably low or clearance is obtained from their hematologist. All such decisions are made with appropriate documentation and, when needed, interdisciplinary input to ensure patient safety.

4. Transparency and Communication: Therapies are presented with honesty and respect for both traditional wisdom and scientific inquiry. While curative outcomes are not guaranteed and remain subject to further validation, the historical and experiential basis of many treatments is acknowledged. Homeopathic and herbal therapies are offered with full disclosure of ingredients and intent, and may be used as adjuncts, or, when chosen by the patient with informed consent, as primary therapies only when the patient is fully informed of conventional options, prognosis, and risks, and such choice is documented and co-signed by the lead physician. The emphasis remains on open dialogue, shared decision-making, and clarity of therapeutic goals.

5. Practitioner Boundaries and Scope of Practice: Complementary practitioners operate within the limits of their professional training and licensure, contributing their expertise as part of a collaborative care team. They do not independently advise on starting, stopping, or altering conventional medical treatments. If such questions arise during a consultation, they are brought to the attention of the lead physician and documented appropriately in the medical record to ensure coordinated, safe care.

6. Documentation and Monitoring: Complementary interventions are recorded in the electronic medical record using simple, standardized templates that capture key details such as rationale, formulation, dosage (when applicable), intended goals, and any observed effects. Documentation supports continuity of care and shared understanding across the clinical team. As the department grows, periodic case discussions or informal peer reviews may be introduced to help maintain quality and support reflective practice.

7. Innovation and Institutional Contribution: Practitioners are encouraged to draw on traditional knowledge, clinical experience, and individual patient needs to propose novel therapeutic formulations. When deemed potentially beneficial, such contributions may be submitted to the institutional pharmacy for review, with any clinical use occurring under physician oversight. This process supports innovation while ensuring that all therapies align with standards of transparency, safety, and collaborative accountability. Any novel formulation will be reviewed under institutional CAIM protocols, and not distributed outside clinical context.

Modest commercial activity that supports the viability of practitioner-led innovations should not be excluded under overly broad interpretations of conflict of interest. When carried out transparently, without coercion, exaggerated claims, or undue influence, and with full disclosure to patients and the institution, such contributions can strengthen both clinical care and academic growth.

Their ethical grounding lies in their transparency, patient-centered intent, and alignment with the department’s mission: advancing integrative, accountable care and fostering the development of new therapeutic formulations and inventions.

Dismissing the expertise of department members in the name of rigid conflict-of-interest policies would not only be a disservice, it would risk obstructing the very innovation the department was created to support.

The Economic and Clinical Imperative:

The establishment of a CAIM department is not a luxury, it is a timely, evidence-supported strategy for clinical and financial sustainability. As conventional medicine grapples with rising costs, therapeutic plateaus, and growing public disillusionment, CAIM offers measurable, system-level solutions.

A large multi-center cohort study found that patients receiving integrative therapies experienced a 43% reduction in hospital admissions and over 58% fewer inpatient days than matched controls [8]. These gains are not theoretical, they translate into shorter stays, increased bed availability, lower per-patient costs, and improved care flow. The most notable benefits were seen in areas like chronic pain, anxiety, and stress-related disorders, where conventional approaches often stall [9].

Meanwhile, 30–50% of adults in high-income countries already use some form of complementary or alternative care, frequently outside formal clinical settings and without their physicians’ knowledge [3,4]. This disconnect fuels the rise of a parallel, unregulated, and potentially unsafe industry. When hospitals ignore this demand, patients turn to informal markets where misinformation spreads, safety is compromised, and continuity of care is lost. The result is erosion of trust, not in pharmaceutical companies, but in hospital.

CAIM departments not only close this gap, they meet patients where they already are. Hospitals that have embraced integrative models report higher patient satisfaction, stronger community loyalty, and a return to whole-person, preventive, and culturally aligned care [6]. Clinicians also benefit. CAIM environments are consistently associated with lower burnout, richer patient relationships, and broader therapeutic flexibility, renewing purpose and improving retention [10].

Integrating CAIM is more than a clinical upgrade, it is a marketable signal of institutional leadership in an era of shifting expectations.

The Political and Strategic Wake-Up Call:

If the clinical case is compelling, the strategic warning is urgent. On June 9, 2025, U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a prominent vaccine skeptic, fired all 17 members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). This was not an isolated decision, it was the latest tremor in a broader political earthquake. Under a second Trump administration, scientific consensus is being dismantled, public health agencies are being hollowed out, and decades of biomedical orthodoxy are being rewritten by executive fiat.

In this volatile landscape, hospitals, not pharmaceutical companies, are on the front line. When trust in science falters, it is the local health systems and clinicians that patients confront with their confusion, fear, and frustration. If institutions remain tethered to outdated, pharma-centric models of care, they may find themselves scapegoated for a crisis they didn’t create, but failed to prepare for.

This is where the Kodak analogy becomes painfully real. Kodak once owned the film photography market. It even invented digital imaging. But it failed to act, not due to ignorance, but out of fear of disrupting its own status quo. Hospitals today face the same crossroads. Dismissing CAIM as fringe or irrelevant, while millions of patients vote with their feet, is not caution. It’s capitulation.

The decision not to diversify is not ethically neutral. It is a strategic miscalculation with existential consequences. Loyalty to the pharmaceutical-industrial model will not protect hospitals from political disruption, public backlash, or market abandonment.

But there is still time to lead. A thoughtfully implemented CAIM department is not just good medicine, it is future-proofing. It tells the public: We are listening. We are evolving. We are not afraid to serve with both science and wisdom. It tells staff: We trust your clinical judgment and are restoring depth to the healing mission.

Hospitals now face a binary choice:

Path | Outcome |

Resist | Relevance fades, trust collapses, patient volumes shrink—and the institution becomes the next Kodak. |

Adapt | Reclaim leadership, meet real-world patient needs, and secure a resilient, future-aligned care model. |

This is not a passing trend, it is a turning point:

Hospitals that hesitate now may lose their competitive edge and find they no longer have the opportunity to catch up later. Despite rapid advances in diagnostics, therapeutics, and digital technologies, modern healthcare systems remain burdened by rising costs, escalating rates of chronic disease, and growing patient dissatisfaction.

This proposal aligns with key health policy priorities across major global blocs. In ASEAN, it supports the Vision 2025 agenda to integrate traditional and complementary medicine into universal health coverage frameworks (14). Within the African Union, it echoes the African Traditional Medicine Strategy, which promotes the institutionalization and regulation of indigenous therapies (15). Across these regions, a department of CAIM offers a sovereign, scalable model, empowering nations to strengthen primary care, reduce pharmaceutical dependence, and align medical practice with cultural values makes healthcare more accessible and responsive to patient demand.

National Relevance and African Implementation Pathways:

Across Africa, governments are working to deliver healthcare that is accessible, culturally resonant, and financially sustainable, while confronting rising costs and persistent rural health disparities. A Department of CAIM offers a practical solution already aligned with continental priorities.

The African Union’s Traditional Medicine Strategy 2021–2030 calls for the formal institutionalization, regulation, and research of traditional and complementary medicine across member states. This CAIM framework provides an operational vehicle to fulfill that strategy, within hospitals, medical schools, and regional health systems. It builds on indigenous knowledge, strengthens trust in public care, and reduces overdependence on pharmaceutical imports.

For countries like Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and others with longstanding traditional health systems, CAIM departments allow ministries to harness existing practices while raising standards through physician-led governance, safety protocols, and integration into national electronic records. Rather than creating parallel systems, this model embeds trusted therapies into formal care delivery, improving access, continuity, and accountability.

This approach also supports local economies. By formalizing the use of African herbal medicine and supporting indigenous healer networks through training and oversight, ministries can stimulate national production, reduce import burdens, and promote intellectual property development tied to regional biodiversity.

In an era where African health sovereignty and self-reliance are becoming both a political and economic imperative, the CAIM department is not only a clinical tool, it is a strategic asset. Ministers seeking scalable, culturally appropriate, and internationally defensible health reform will find in this proposal a credible and ready-to-launch model grounded in African realities.

Building on Prior Models: What Makes This Proposal Distinct:

The integration of CAIM into hospital-based care has been attempted across several respected institutional and academic settings. Programs at centers such as Memorial Sloan Kettering, Mayo Clinic, and the Veterans Health Administration have demonstrated that safe, patient-centered integrative services can be meaningfully embedded within conventional healthcare systems. In parallel, research by organizations like the RAND Corporation [11] and academic centers including UNC Chapel Hill [12] has helped clarify the structural, regulatory, and epistemological barriers that continue to challenge widespread adoption.

This proposal builds upon those foundational efforts while advancing a more practical, replicable model, grounded in clinical pragmatism and institutional design. Unlike earlier initiatives that often remain boutique in scale or reliant on temporary grants, the framework presented here prioritizes operational feasibility, clinical governance, and financial sustainability. It is built not merely to coexist alongside the biomedical enterprise, but to function as a full-fledged department, complete with credentialed roles, integrated documentation, safety protocols, referral logic, and outcome tracking.

Several features distinguish this model from prior attempts:

Physician-led, co-managed structure: Positions CAIM within the formal medical hierarchy to ensure patient safety, institutional trust, and meaningful collaboration, while preserving appropriate autonomy for licensed complementary practitioners.

Structured referral logic (S.C.O.P.E. model): Provides clear criteria for when and why referrals are made, replacing ad-hoc or anecdotal practices with clinical reasoning and accountability.

EMR harmonization and clinical documentation: Applies the same standards of documentation, coding, and quality assurance to CAIM services as to mainstream medical departments, ensuring parity and continuity of care.

Culturally inclusive therapeutic scope: Accommodates globally recognized modalities like acupuncture and Chinese medicine, as well as regionally relevant systems such as Ayurveda, Hikmat, and Unani, supporting both diversity and relevance.

This framework is offered not as a fixed or prescriptive model, but as a living clinical blueprint, informed by real-world successes, mindful of persistent challenges, and responsive to the evolving expectations of patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems.

Conclusion and Next Steps:

This proposal outlines a clinically grounded, ethically structured framework for establishing a department of CAIM within a modern healthcare institution. By integrating evidence-informed complementary modalities into the biomedical setting, it addresses longstanding gaps in patient care, particularly for conditions that remain underserved or inadequately managed by conventional approaches alone. The model is designed to support safe, accountable, and culturally responsive care within a structure that is fully compatible with hospital systems.

This framework offers a replicable foundation for institutions seeking to implement whole-person, interdisciplinary care in a way that is both operationally viable and professionally credible.

Part Two of this article will focus on the operational implementation of the department within a real-world institutional context. It will detail infrastructure requirements, team-based clinical workflows, EMR integration strategies, governance structures, reimbursement pathways, and systems for tracking clinical outcomes. Drawing on lessons from established integrative programs across North America and Europe, it will include visual schematics and practical guidance to support translation of this model from concept to clinic.

In an era marked by rising rates of chronic disease, therapeutic burnout, and growing demand for culturally competent care, this proposal offers a timely and actionable path forward. It is designed to be medically sound, ethically governed, and institutionally replicable, positioning hospitals to lead, rather than lag, in the future of integrative health.

Acknowledgment:

This article was written with AI assistance. All claims are supported by credible, peer-reviewed references, which were validated for accuracy and authenticity. The AI synthesized information were reviewed by authors, ensuring scientific integrity throughout. In the event of any inadvertent errors, the responsibility lies with the AI/authors, and corrections will be made promptly upon identification. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr Tahira Khalid, for her thoughtful review and invaluable feedback. Her expertise and guidance have played a pivotal role in refining and enhancing this article.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The author is the developer of a herbal formula and the owner of Dr. Q Formula/Insulinn LLC. However, this affiliation has not influenced the content, analysis, or conclusions of this article

Author’s Note on Scope and Intent:

This proposal does not advocate the replacement of evidence-based conventional care with CAIM modalities. All complementary interventions are intended to supplement, not supplant, standard clinical practice, and are implemented within a physician-governed, ethically reviewed, and fully documented medical framework.

References

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4573565/

World Health Organization. Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924151536

Posadzki P, Watson LK, Ernst E. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13(2):126–131. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23681857/

Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: A systematic review. J Integr Med. 2012;10(3):208–219. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22438782/

Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Charns MP, Kligler B. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation: A Progress Report. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf

Mayo Clinic. Integrative Medicine and Health – Overview. https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/integrative-medicine-health/sections/overview/ovc-20464567

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Integrative Medicine Service. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/diagnosis-treatment/symptom-management/integrative-medicine

Chao MT, Tippens KM, Connelly E. Utilization of Group and Individual Acupuncture Services in an Integrative Medicine Program. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(S1):S70–S77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25749600/

Herman PM, Poindexter BL, Witt CM, Eisenberg DM. Are Complementary Therapies and Integrative Care Cost-Effective? A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001046. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22945962/

Dossett ML, Cohen M, Kligler B, Wayne PM. Integrative Medicine Program Enhances Patient and Clinician Experience and Well-Being at Academic Health Centers. Glob Adv Health Med. 2018;7:2164956118818043. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30428106/

RAND Corporation. Hospital-Based Integrative Medicine: A Case Study. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health; 2006. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG591.html

University of North Carolina. Integrating CAM into Conventional Practice: Barriers and Best Practices. UNC School of Medicine, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2018. https://www.med.unc.edu/phyrehab/pim/wp-content/uploads/sites/615/2018/03/Integrating.pdf

StartupTalky. Kodak Case Study – How They Went Bankrupt. https://startuptalky.com/kodak-bankruptcy-case-study/

ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Post-2015 Health Development Agenda (2021–2025). Jakarta: ASEAN; 2024. Available from: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/E-Publication-ASEAN-Post-2015-Health-Development-Agenda-for-2021-2025-1.pdf

African Union Commission. Africa Health Strategy 2016–2030. Addis Ababa: African Union; 2016. Available from: https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32895-file-africa_health_strategy.pdf

Excellent but too long. Simplify by highlighting each principles with a few words. Brevity is the soul of wit, said Polonius in Hamlet.